Why I Disappear

I disappear for weeks at a time (ok, sometimes months). The work asks for that. When I step out of the social current, I step into a different register of attention, one where perception stops skimming and starts opening. This register crystallizes into whatever I am making; people who live with my paintings have named the effect without being prompted. They describe a steadier air in the room, a sense of space returning, and that (along with the intrinsic reward of extended deep focus) motivates me to enter the threshold again and again.

Day one is always negotiation. My hand reaches for the phone before my mind remembers there is no phone, and I can feel the muscles behind my eyes searching for the next thing. If I stay with that restlessness, it burns off into something quieter, the way a lake loses its chop when the wind drops.

The first days my attention reaches for its usual handles, my mind tries to keep me in circulation, and some part of me worries about what my silence will be made to mean. I accept the friction because the outcome is concrete. The work returns with more clearance around it, and that clearance keeps working long after the studio period ends.

“I step into a different register of attention, where perception stops skimming and starts opening.”

I have been training this for most of my life. In my twenties the disappearances were clumsy and urgent. Over time I learned the difference between hiding and going in, and the threshold became less a dramatic choice than a method. It functions like an extended field trip taken inside the same life, where inputs are reduced enough for perception to regain its natural sharpness, and where my own signal can reappear without being drowned out.

Accessibility is treated as a virtue almost everywhere. A decent person replies. A serious person stays reachable. When I step out of that current, social pressure gathers at the edges, and guilt tries to translate that pressure into a story. People wonder if I am angry, fragile, or staging distance. Even friends who love me sometimes treat silence as a problem that wants a quick solution.

What they do not see is how literal my sensitivity is. Stimulation stacks in my body like static. I can keep functioning while it accumulates, yet the inner field becomes grainy. Subtle distinctions flatten. Composition starts taking cues from whatever is most insistent, even when the insistence is coming from inside my own mind.

So I leave the room.

The phrase “hermit” can sound romantic from the outside. From the inside, it is mostly logistics and restraint: fewer conversations, fewer images. I stop taking in other people’s cadence so my own rhythm can return—but the mind bargains anyway. It offers productivity fantasies, rehearses social anxieties, reaches for little loops that make the day feel populated. I let that happen, and I keep the conditions simple.

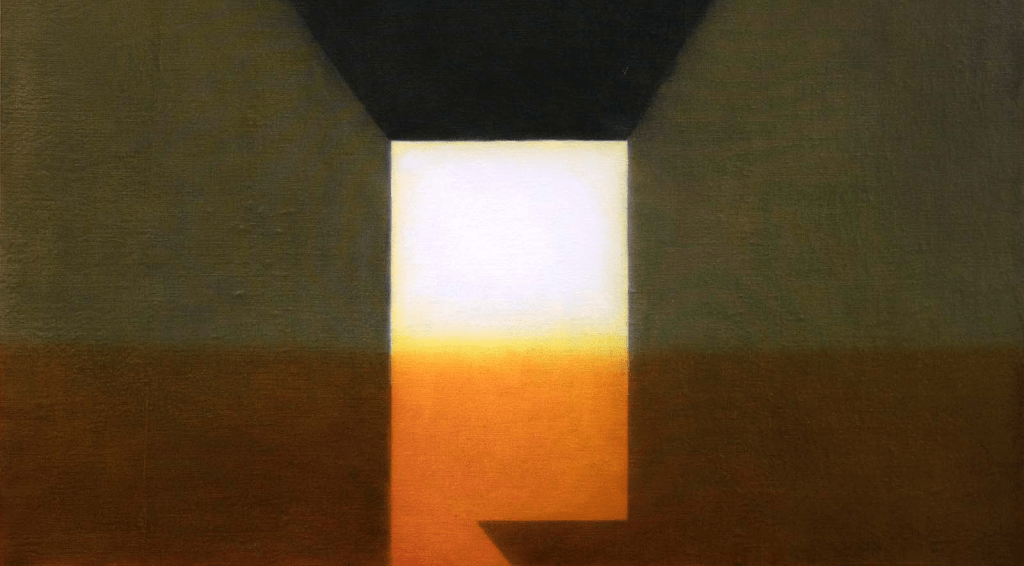

This is why I think in terms of interface. An interface translates between systems. It is the boundary where one kind of reality becomes legible to another. Solitude is the boundary I use, because it translates between ordinary life, with its constant micro-demands, and the kind of attention that can hold a space open without rushing to close it.

“Attention stops behaving like a beam and starts behaving like a field.”

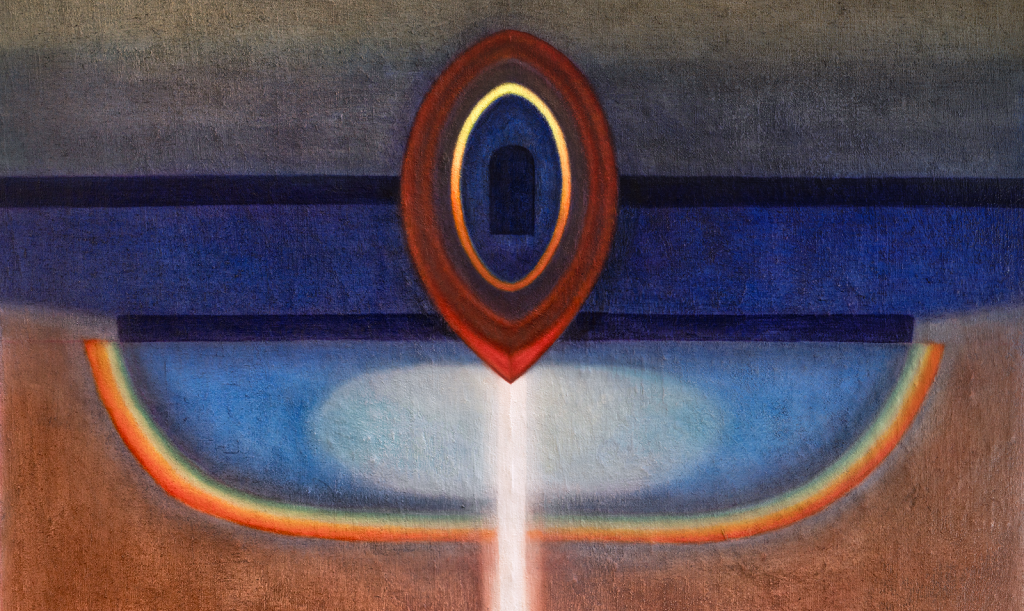

At some point the air stops feeling crowded, even though nothing has moved. Attention stops behaving like a beam and starts behaving like a field, and perception moves into a different octave. Space appears in the in-between. I begin to see through, rather than only at. That is where composition starts triangulating upon a truth, regardless of whether the output is pigment, frame, object, or screen.

Right now I am in a season of painting. Six works at a time, completed slowly, the surface built through long accumulation. Paint is a demanding interface in itself. It holds time. It asks me to remain with a single decision until it ripens into the next one. Those constraints keep training the same faculty I am describing here, the ability to stay with the in-between without filling it too quickly.

And I can already feel the work beginning to unhook from the category. After this year, the paintings will not be the only site where this spaciousness gets made. I am moving toward proto-interfaces, small hand-worked frames that hold an empty center or a simple field, objects designed to be used, returned to, handled. The frame becomes a boundary you can stand near. The emptiness becomes an active center. Small handmade pieces will carry the same question in a different grammar, and later those frames will hold generative fields, iterative compositions that can change without losing their stillness.

My criterion is simple. If attention has to be coerced, the work won’t last.

I notice how much culture is built to click quickly. A clever symbol. A compressed story. A premise that lands immediately. I understand the appeal of that economy, and I don’t think it is immoral. I just know what it does to my own attention. The quicker the click, the sooner the looking ends, and the surface becomes a delivery vehicle rather than a place.

“I want the work to remain usable across years, across whole seasons of a life, sometimes across lifetimes, as it moves from one person to another.”

I work slowly because I am trying to make things that keep looking back. Obvious narrative cues get reduced, because I want the work to remain usable across years, across whole seasons of a life, sometimes across lifetimes as it moves from one person to another. The form can be a painting, a framed emptiness, a generative field, a ritual object. The point is consistent. The work should hold a threshold without requiring anyone to perform a threshold-crossing in public.

Disappearing has a cost. It means delayed replies, missed gatherings, the stiffness of re-entry. It means trusting that the people who belong in my life will read my absence as weather rather than as accusation. When I return, the world can feel loud. The first café can feel like a stadium, and conversation can feel percussive. I re-enter slowly, and I try not to punish the world for being what it is.

“Disappearing has a cost.”

Over time, the studio has taught me something simple. The quiet area, the empty-looking field, the margin that appears to be doing nothing, ends up doing most of the structural work. Counterspace holds the composition the way a room holds a gathering. The edge becomes active. The emptiness becomes load-bearing.

If you live with one of my paintings, you already know what I mean, even if you have never used my language for it. You pass it on the way to the kitchen, or you catch it out of the corner of your eye while you are thinking about something else, and the day has a little more margin around it. The threshold stays on the wall, waiting for your attention to arrive when it can.

Leave a comment